Orchard

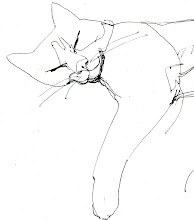

A lithograph from Dapnis and Chloé

by Marc Chagall

The extract from L’Immoraliste that I have translated (below) describes a pivotal moment in Gide’s novel, evoking as it does the narrator’s increasing awareness of the reawakening of his senses after his long and disabling illness.

Michel describes his explorations of the palm groves that he and his wife discover after erring from the path that they have been following during a walk through the town in north Africa where they are staying. A break in the high wall that flanks the path, and the glimpse it offers of the luxuriant landscape of the gardens enclosed and hidden by this same wall, is enough to tempt the couple to deviate from their course. Who can blame them? The lush greenery brings into sharp contrast the sterility of the parched mud floor and high mud walls that confine the usual path; the palm grove is a true oasis – a place of beauty that offers respite and resuscitation for the senses otherwise withered by the mundane.

The garden is surely the eternal symbol of rebirth and regeneration and enclosed as it is here by a high wall that shields it from any harsh, intrusive and censorial gaze, this garden seems symbolic of the womb itself. Michel takes retreat and, closing his eyes, withdraws further from the external world to an inner place where he finds he can just listen to his senses. He quickly becomes intoxicated by the soothing sounds of the doves cooing, the rippling stream, the breeze rustling through the tops of the trees, which echoes the stirrings that he feels as his senses are roused from their somnolence. Disarmed by his repose and contemplation, he is further seduced by the dulcet tones of a flute that the goatherd boy is playing: as his inhibitions are anaesthetized, he succumbs to the delight of his physical arousal.

Later Michel deliberately returns alone to the oasis where he listens as the boy enchants him further with his explanations of how he knowingly watches over his charges, carefully ensuring that their needs are satisfied but only when necessary. The boy, it seems, both arouses and assuages desires. It’s not difficult to see why, despite the obvious lyricism of his prose, the representation that Michel makes of a paradise where young boys enchant and stand ready to meet the needs of those in their care, provoked some controversy amongst Gide’s peers. The inferences suggest more questions than they answer. Moreover, the seductive and sensual figure of a boy playing a flute in a fertile landscape is surely a further evocation of the notion of temptation and transgression. Is Gide really casting the goatherd boy in the role of serpent in this Garden of Eden?

Leaving the ambiguities to one side, this passage is, for me, very evocative of some of Chagall work - no doubt because of their lyrical treatment of pastoral imagery. The series of lithographs on the story of Daphnis and Chloé, the foundling shepherd children that, in their innocence, are troubled as their friendship turns to love, particularly comes to mind.

Michel describes his explorations of the palm groves that he and his wife discover after erring from the path that they have been following during a walk through the town in north Africa where they are staying. A break in the high wall that flanks the path, and the glimpse it offers of the luxuriant landscape of the gardens enclosed and hidden by this same wall, is enough to tempt the couple to deviate from their course. Who can blame them? The lush greenery brings into sharp contrast the sterility of the parched mud floor and high mud walls that confine the usual path; the palm grove is a true oasis – a place of beauty that offers respite and resuscitation for the senses otherwise withered by the mundane.

The garden is surely the eternal symbol of rebirth and regeneration and enclosed as it is here by a high wall that shields it from any harsh, intrusive and censorial gaze, this garden seems symbolic of the womb itself. Michel takes retreat and, closing his eyes, withdraws further from the external world to an inner place where he finds he can just listen to his senses. He quickly becomes intoxicated by the soothing sounds of the doves cooing, the rippling stream, the breeze rustling through the tops of the trees, which echoes the stirrings that he feels as his senses are roused from their somnolence. Disarmed by his repose and contemplation, he is further seduced by the dulcet tones of a flute that the goatherd boy is playing: as his inhibitions are anaesthetized, he succumbs to the delight of his physical arousal.

Later Michel deliberately returns alone to the oasis where he listens as the boy enchants him further with his explanations of how he knowingly watches over his charges, carefully ensuring that their needs are satisfied but only when necessary. The boy, it seems, both arouses and assuages desires. It’s not difficult to see why, despite the obvious lyricism of his prose, the representation that Michel makes of a paradise where young boys enchant and stand ready to meet the needs of those in their care, provoked some controversy amongst Gide’s peers. The inferences suggest more questions than they answer. Moreover, the seductive and sensual figure of a boy playing a flute in a fertile landscape is surely a further evocation of the notion of temptation and transgression. Is Gide really casting the goatherd boy in the role of serpent in this Garden of Eden?

Leaving the ambiguities to one side, this passage is, for me, very evocative of some of Chagall work - no doubt because of their lyrical treatment of pastoral imagery. The series of lithographs on the story of Daphnis and Chloé, the foundling shepherd children that, in their innocence, are troubled as their friendship turns to love, particularly comes to mind.

To see more images of Marc Chagall's work, go to :